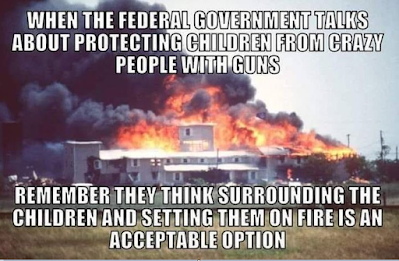

To those who say that citizens armed with AR15s can’t beat the Federal government, I remind you of the events that happened a decade ago…

The Collapse

Violence Ramping Up

It’s an election year. First, some background:

Brandon Fellows was convicted of one felony count of obstructing an official proceeding for his actions at the January 6 protest, and was sentenced to 36 months in prison.

Federal prosecutors sought a top-of-the-guidelines sentence o 37 months in prison – describing him as a “cheerleader” for violent rioters and saying he could be expected to be back at the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2025, if his preferred candidate again doesn’t win.

You bet your ass, if the left cheats another election, many people will be back to protest the results- and next time, you can expect them to be armed. They won’t repeat the mistakes of 2021.

Anyway, Fellows also got an additional 5 months for contempt of court for calling the proceedings a kangaroo court being run by a bunch of Nazis. Since the Feds had held him in pretrial confinement for 32 months before his conviction, he was out less than a year later.

“You have repeatedly made a mockery of these proceedings,” McFadden said, noting Fellows had shown the “height of contempt” for all three branches of government and had “flagrantly lied” on the stand at trial. McFadden also pushed back against Fellows’ belief that he was the victim of a “grand conspiracy” against him.

It turns out that he was right, since SCOTUS declared in June that using the obstruction of an official proceeding statute in the case of the J6 defendants was unconstitutional. Fellows is now appealing the conviction, and is likely going to get it tossed out. Until then, he remains a convicted felon. As if “felon” really means anything nowadays, since we are letting rapists, armed robbers, and other violent criminals walk, but using felony charges for political reasons, but I digress.

This guy acted more like a prisoner in a POW camp than he does a criminal. He has my respect. From the Code of Conduct:

If I am captured I will continue to resist by all means available. I will make every effort to escape and to aid others to escape. I will accept neither parole nor special favors from the enemy.

I myself am holding all three branches of the Federal government in contempt. Our national government is truly evil- we know that they have experimented with biological warfare by using them against our fellow citizens without their knowledge. We know that they care only for power and wealth. Anyhow-

So that’s the background. Now to the point of today’s story. Fellows was eating dinner in a DC restaurant with journalist Connie Clifford. (Note that the report calls her “right-wing journalist Connie Clifford” but Newsweek doesn’t ever refer to CNN reporters as “left-wing journalist Chris Matthews.”) Fellows was wearing a MAGA cap and talking about the progress of his case. A nearby commie couple was annoyed and a verbal argument began, with Clifford catching the argument on camera. The couple told him he was “not welcome with your Trump bullshit.”

The female of the couple slapped Fellows in the face, and Fellows pushed her away. At that point, the woman’s companion began punching Fellows in the face.

The violence is ramping up again. They want us dead- they want you dead. Prepare for what is to come. Things are going to get much, much worse. They are going to try and kill or enslave you. Be ready for that.

The Collapse

Ambush

I post this to show you an interesting situation. Watch the video below and see comments below:

To begin with, the cops during the traffic stop were taunting the intoxicated man and attempting to escalate the situation so they could get him to do something that would permit a felony arrest. They were being assholes. It’s easy to be the bully when you are armed and outnumber the unarmed target of your abuse three to intoxicated one.

The intoxicated man decided that he was going to get revenge, called 911, and executed an ambush. Two officers were killed and one wounded.

That’s all I want to talk about in this case. Instead I want to point out that one intoxicated man successfully ambushed three cops. Now ask what would happen when cops decide to exceed the tolerance of the citizens they are sworn to serve. What could two, three, or ten armed citizens accomplish once they decide that they are going to hunt?

Economy

Collapse

As empires collapse, the government employees/legislators begin to loot the treasury in preparation for the coming hard times. I believe that we are there. In support of this, I offer the increasingly blatant examples of Congress making hundreds of millions, the Bidens selling access, this morning’s story about CBP agents on the take, and someone in the Arkansas Department of Education creating a fake $66 million contract that, according to the vendor, doesn’t exist.

I have been posting on this since 2009, nearly since this blog began.

- Reagan borrowed his first trillion in 6 years

- George HW Bush borrowed his first trillion in 3 years, and he increased the National debt by 170% in four years.

- It took President Clinton 3 and a half years to borrow his first trillion dollars. All told, he borrowed $1.2 trillion in his first term, and $600 billion in his second. He increased the national debt by 140% in eight years.

- President George W Bush borrowed his first trillion dollars in two and a half years. He borrowed his second trillion a year and a half later. Another two years, another $1 trillion. All told, President Bush borrowed $5 trillion in 8 years, increasing the national debt by 187%.

- Obama borrowed his first trillion in 13 months.

- Trump borrowed his first trillion in just over 7 months. In all, he borrowed about $8 trillion in four years.

- Biden has borrowed $6 trillion in the three and a half years he has been in the Oval office. Now we are borrowing a trillion dollars every 5 and a half months.

The US treasury has borrowed $24 trillion in the past 15 years.

Cops

Good Work, if you can get it

A Customs and Border Protection Officer has been convicted by Federal jury of receiving bribes in exchange for allowing drug and illegal immigrant laden vehicles to enter the US.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office estimates that George was paid between $300,000 and $400,000 during the time he worked with traffickers. Among the purchases George made with the bribe money include cars, motorcycles, and jewelry, prosecutors said.

The Collapse

The Left is Pissed

I will still say that I believe that the Democrat candidate, whomever that turns out to be, will be declared the winner in the 2024 election. After that, what comes next? Here are some clues:

Like most dictatorships, the left only has respect for a court that rules the way that they want it to. Once the court is no longer serving leftist ends, expect there to be big changes. However, the President is simply ignoring the decisions of the court that he doesn’t like. See student loan forgiveness.

This tells me that the rulings coming out on bump stocks, abortion, and braces are simply tools to rile up the leftist base, so the court is permitted to continue. Still, expect to see some changes after the election.

The Collapse

Quote of the Day

The Civil War you imagine and fantasize about isn’t going to happen the way you think. There won’t be “front lines”, there probably won’t even be an insurgency, not in the beginning, anyway.

What you’re going to see is “The Troubles” on meth and steroids (And if you’re too young or too stupid to know what those were, fire up the Googlemachine.)

It’s going to be a lot of assassinations, kidnappings, and disappearances. Retributions and retributions for retributions. It’s going to be bombings and quick drive by skirmishes. The military will have next to no role in it other than on the ground checkpoint monitors and hardening their own instillations.

Your F-15 pilot won’t fly missions after the last time his squad mate did, and landed to find his family laying in the street.

It’s not going to be the far right vs the government alone. It’s going to be the militant left against the militant right, and the government. Battles are going to be fought everywhere and nowhere.

A friend of mine thinks it’ll be more like “The Purge” petty feuds with the HOA or neighbors finally take vengeance for some perceived wrong.

And I’m here to tell you, it’s going to be both. But I assure you, the military is going to be completely impotent in the whole affair. And you will be living in constant fear.

This is what you keep pushing for and taunting people towards, you’re just too fucking stupid to know it.

Purge opposition

This is how Liberty Dies

I usually comb the Internet and social media in search of blog fodder. That is hard to come by today, because the Internet and the news cycle is dominated by the left cheering that the sitting President was able to toss his main political opponent in prison. This makes it difficult to find anything to write about that isn’t simply TDS porn.

Trump understood something that Biden does not: Throwing your political rivals in prison may make your supporters cheer with glee, but at the cost of destroying the very rule of law that always made this nation the shining beacon on the hill. That is no more…

We have officially joined the long list of nations where votes don’t matter, and dictators have their political opponents jailed or killed.

The Collapse

Nothing is Changed

The verdict in the Trump case isn’t a surprise. For four years (since before the 2020 election), I have said that they will do whatever it takes to keep Trump out of office. That opinion hasn’t changed.

There are those who think that the left WANTS Trump to be there in the White House to serve as a fall guy when things go tits up. I don’t think so. These guys think that they are the smartest ones in the room. After all, they get away with their crimes every. single. day.

- They are blatantly and openly accepting bribes.

- They are blatantly and openly molesting children.

- They are openly engaged in insider trading and rigging the stock market.

- and more. I’m sure you can think of some.

Yet their side still supports them, and no one on the “other” side even mentions trying to stop them, because the Republicans are just as corrupt and invested in the system as they are. They will keep on stealing, lying, cheating, and sucking off of the public teat until there is no more treasure to be had.

It’s been obvious that this nation will fail for decades now. Anyone who has the ability to run a calculator could see it. All we can do at this point is be prepared for what is coming. The left is still openly following the CIA insurgency manual- the CIA literally wrote the book on how to overthrow a government, and that is exactly what is happening here.

A word of advice- the show trials phase of the insurrection is here.

The show trials that I began predicting on July 6, 2020, with the two posts titled “Roots of an insurgency, part 3,” and “Tying it all together.” From the “Roots” post:

Once the last phase begins, totalitarian elites let loose their inclination to brutally eliminate their perceived enemies. Once this phase begins, things happen very quickly. The entire country will collapse in a matter of weeks.

Violence is considered a means to achieving the goal of centralized power. There is not even a pretense of due process or respect for free speech.

Then there is the Tying it all together:

This is also the stage where purges begin, books are burned or rewritten, and the history of the old regime is destroyed. This prevents any sort of “counter revolution” from gaining any traction.

Things are going to get worse as we approach the election. It isn’t just Trump.

- Harrison Floyd is getting tossed in prison for disputing the results of the Georgia 2020 election.

- FBI informants who come forward about the corruption of the Biden family are getting throw in the gulag

- They are working their way down the list

Develop your own lists. Have a list of canaries- people who are outspoken and influencing others. When they start to disappear, run. Have a list of people in your neighborhood or families who may be subversives or informants for the left. Know what to say to them and not say that will get you informed upon.

Things will begin to unravel with nearly blinding speed.